It's Not Right, But It's Okay

You know in the Glee version when Blaine sings "I can PAY my own rent!"

Whitney by Richard Avedon, 1987 - courtesy of Blessed Images by Kyrell Grant

Whitney Houston’s voice is the first sound I remember loving. I’m sure I loved other sounds like my parent’s laughter or a Tickle Me Elmo but this sound has a narrative attached; my mom tells me I sang along to Whitney before I could speak and just like that I have a sense memory of her voice ringing clearly in my tiny infant head. The simultaneous conviction and softness of her "ooh" vowel alone, her melisma effortlessly meandering but always finding a way home. I didn’t just want to hear her voice, I wanted to emulate it, to embody it.

As a kid I performed her ballads in the car for my family. I channeled the emotions of songs far beyond the scope of my 6 year old lived experience, amusing my grandma as I mournfully sang "All At Once" like I’d drifted on that lonely sea myself. The first time I sang for a crowd was a recital performance of “The Greatest Love of All”, just a child believing children are, in fact, the future. Singing along with Whitney's performances was my greatest high and my favourite moments were when I couldn’t tell our voices apart; for one sustained note I’d match her controlled vibrato and felt like I was flying. I dreamt what it would it be like to have a voice so undeniable, so emotive and powerful and dexterous that it is a language of its own, expressing what cannot be articulated.

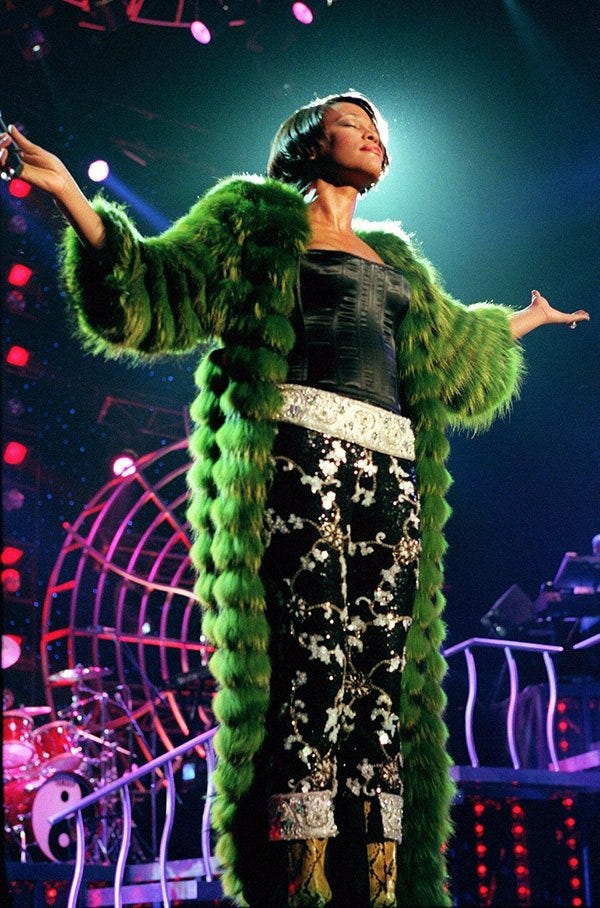

My first concert was when my parents took me to the My Love Is Your Love tour at the Molson Amphitheatre in 1999. It was the first time I experienced sharing a vibe with an audience and performer. I felt in relationship with Whitney, and it was a difficult relationship to define. Even at the age of 8 I clocked that she was performing under some influence, that she was struggling somehow but still was here with us on this night, sharing her voice. Until this point Whitney had transcended personhood to me, she was an idol, an infallible star. Yet here she was, a material woman, running around and sweating and making jokes in the middle of songs. At one point she brought out Bobbi Kristina to sing with her and I took turns singing along with each of them, the legend in a Dolce and Gabbana coat and her 6 year old angel telling us clap your hands y’all, it’s alright.

Years later I’d meet a friend at the Hot Docs Cinema to see Whitney: Can I Be Me, a documentary that incorporates behind the scenes and onstage footage from the European leg of her 1999 tour. Rumours swirled about Whitney’s behaviour on this tour and the film relies predominantly on archival footage to make suggestions, if not conclusions, about the source of Whitney's struggles with her faith, her bisexuality, and her drug use. There she is, my hero goofing around with Bobby Brown and Robyn Crawford, flopping down on the couch to watch Set It Off together. There she is, my hero in the green fur coat I remember seeing draped around her shoulders but this time we follow her offstage and she is shaking. I feel grateful for the footage of her being natural and having fun; it feels like more time with her. I feel revulsed by the existence of this unauthorized documentary, knowing even in her death her legacy is subject to media sensationalism. The line between exposition and exploitation is finest when it comes to depictions of women struggling with fame. The distinction blurs between our love of person and idol; of performer and product. They must be impeccable, for Diane Sawyer stays waiting in the wings to provoke any hint of vulnerability.

Do you remember where you were when you heard Whitney Houston had died? I was at a dress rehearsal for a university production of The Who's Tommy – imagine the state of a room full of singers upon hearing the news. It was a time when you remembered the physical context of hearing about celebrity deaths; now it isn't a matter of how you're going to hear about it as much as what kind of tweet will deliver the news. At the time of her passing, the public figure known as Whitney Houston was a caricature. You were more likely to see her lampooned by Maya Rudolph or Debra Wilson than championed or defended. Rudolph returned to host SNL on February 18th, 2012 and faced "really gross" expectations that she would reprise her popular impression even though Whitney’s funeral was that same night.

As I was unpleasantly reminded recently, the cover art for the 2018 Pusha T album "Daytona" is Whitney Houston's bathroom. Kanye West insisted on using the photograph, originally taken in 2006 by Bobby's sister Tina Brown and sold to the National Enquirer. Josie Duffy Rice wrote about this thoroughly and thoughtfully for The Atlantic:

Dying of addiction is a particular cruelty—it kills you and then haunts the collective memory. If you die by heart attack, or cancer, or in your sleep, it’s a tragic postscript to your life story. If you die of addiction, it is your life story. It becomes the whole plotline. Whitney Houston was the greatest pop vocalist of her time, a luminescent woman, joyful, a black woman built of the church. But as an addict she became a sideshow—mocked in her long struggle, and ogled in her death. How she lived has been overawed by how she died, so much so that the scene that led to her death can now be packaged, like her music, as a commodity.

Earlier this month, Disney+ finally got their act together and acquired the Whitney Houston produced Cinderella, starring Brandy. Watching it now feels like a gift, a hand extending from the past to hold onto. I felt so emotional seeing Whitney as the Fairy Godmother, popping in and out of that carriage, doing some truly incredible green screen work. That's essentially how I remember her: regal, glowing and projecting 1997 CGI spirals out of her fingertips. She was touched by magic.